I’d like you to take a look at a video:

This is the first TV spot for Tim Burton’s Frankenweenie, the director’s most recent release that’s by all accounts imaginative and full of heart. It is a full-length, stop-motion remake of the short film that lost him his first job with Disney back in 1984.

After his dismissal from Disney, Burton went on to much bigger and better things, as both a director and producer. The list of his most beloved films is long by any standard: from Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure and Beetlejuice, to Batman, Nightmare Before Christmas, and Ed Wood. Even some of his less successful endeavors – Sleepy Hollow, Big Fish, The Corpse Bride – are worth watching for the detail and imagination put into every moment. Even the self-indulgently weird Planet of the Apes had me hoping for a sequel.

All of this to say, like many people who grew up in the past three decades, I am a fan of Tim Burton’s movies, especially his classic period. No one can tell me that the man hasn’t produced an amazingly impressive body of work: he is a legend.

That said, I wasn’t all that interested in Frankenweenie. I haven’t been a fan of Burton’s family films of the past ten years or so. Moreover, as an owner of an older dog, I’m not too enthusiastic about a movie dealing with dead pets. People? Sure, you can have all the dead people you like. (Paranorman, for example, was pretty great.) But not puppies, sorry. No go. The jokes in the trailer also seemed kind of silly and obvious. I mean, kids’ movie, right? But something else in the trailer just didn’t sit well with me.

At 0:22 in the video, Victor is approached by another boy who says he’s got a bigger problem: one of the giant lizard variety. Asian boy, Charlie Chan accent, easy Godzilla joke? I really wasn’t too thrilled about that bit, which seemed kind of crass to me, but I figured him for a minor character brought in for a one-off joke. What I didn’t know is that the character, Toshiaki, is actually the main antagonist in the film. He’s Victor’s Japanese-immigrant, high-achieving, extremely competitive, and scientifically unethical rival. Toshiaki is a pair of buck teeth and a Fu Manchu mustache away from being a Yellow Peril caricature and he’s the only character of color in the film.

It’s pretty abhorrent. If the character had been an equally broad Black or Latino stereotype, audiences would be up in arms. But it’s just this once, right? Maybe Burton really just wanted to incorporate his love of 1950’s Japanese monster movies? An instance of casual racism in a single film wouldn’t mean that Burton is racist. Unfortunately, it’s not just a single film. Looking over Burton’s body of work, I don’t want to call it racist as such, as it’s just too strong a word. It is, however, definitely exclusionary, at the very least indicating a large and pervasive blind spot.

Try to think of a single, prominent person of color in any Tim Burton film. It’s nigh impossible. Toshiaki isn’t just the only Asian character in Frankenweenie – he’s the only original Asian character in Burton’s entire filmography. He’d be the sole Asian character if not for Ping and Jing in his adaptation of Big Fish: A Novel of Mythic Proportions, and Prince and Princess Pondicherry from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (also based on the book). Regardless of their provenance, they all trade in broad visual and character stereotypes. Black characters hardly fare better: Byron Williams in Mars Attacks!, Harvey Dent in Batman (possibly the only Black man in Gotham), and that’s pretty much it, aside from a few incidentals.

Burton’s films are very much about the outsider, ostracized from majority society. It’s a big part of why his movies have resonated so deeply with geek audiences for so long. His outsiders, however, are outsiders by choice or deed, not by birth, and not by systemic societal exclusion. In his worlds, the majority is White, and the oppressed minority is simply a paler shade of White.

With a few exceptions, Burton has chosen to set his films in a nostalgic, all-White past, or in the case of films like Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure, Batman, and Edward Scissorhands, a not-quite present, not-quite past that leans heavily on nostalgic aesthetics and social structures. His work shows an almost equal fascination with both 1950s suburban America and 1800s England. It would be fair, as a fan, to argue that part of the reason that there are no people of color in Burton’s work is that the settings don’t really allow for them. Technically, one would be right, for fairly ugly reasons. The all-White enclaves of 1950’s America represented the last gasp of segregation. The 19th century was the apex of England’s Imperialism. These were societies that specifically excluded people of color. These are also periods regarded as golden ages in their respective countries, prone to being romanticized.

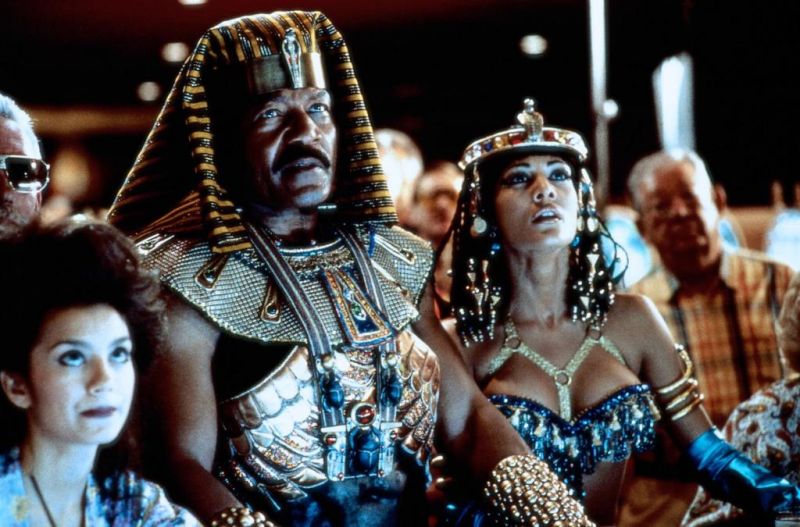

People of color are never part of the communities in Burton’s movies. They come into the worlds of the films to do their job in bit parts, for one scene, then vanish. (Bizarrely, that job is often in law enforcement). They’re not so much characters as plot devices, and often they specifically represent physical power, but practical inefficacy. They are there to establish the relative power of Burton’s outcast protagonists. The police seargent can’t help Pee Wee, and Harvey Dent can’t stop a crime spree. Former heavyweight champion Byron Williams might seem to break the mold here, being a major character, but ultimately his role is to save Las Vegas with his fists.

Then there are the Oompa Loompas. Conceptually, they’re highly problematic. They are, and always have been, merry slaves from an unforgiving continent, bestowed with civilization by a White savior. Oompa Loompas aren’t Burton’s, of course, as they were there both in the original 1964 novel and the 1972 film. Unfortunately, there’s no way to tell Willy Wonka’s story without them, and defusing their problematic elements is nearly impossible. As such, the Oompa Loompas are pretty much the only time it would have been acceptable to have White actors in full-face makeup, if only to avoid the awfully Imperialist overtones of having all of them played by the same, South Asian actor. A race of dark-skinned people who all look alike and are happy to work for room and board? How did no one in the production think this might be a problem?

There’s color blindness, and then there’s sheer tone-deafness.

To put it another way, Burton’s only integrated cast in his entire filmography was for 2001’s Planet of the Apes. It’s his one film to feature multiple actors of color, of different ethnicities, in addition to the White actors. And they all play apes. It just looks bad. You might argue that I’m reading too much into it, that the characters aren’t even human. I would argue that their not being human is exactly my point.

http://youtu.be/hyIiR3tTxDM

Much in the same way the roughly-sewn, frightening, disgusting villain in Nightmare Before Christmas is voiced by a Black man, sings ragtime, rolls dice, and is the only truly evil monster in a community of monsters.

And now there’s Toshiaki. Watch the that trailer again and try not to cringe.

Is the evidence circumstantial? Sure. I want to believe that the problem is one of blindness, or perhaps benign indifference. I prefer to think that the omissions and insensitivity in Burton’s work have to do with his being from a slightly different time, growing up in the shadow of Hollywood in the 1960s, raised on a diet of whitewashed television, and coming from a fairly privileged art-school background. I’d prefer to believe that the racial and cultural composition of his films comes from the works that influenced him.

I love these movies and I love the man’s vision and imagination. If it’s just a blind spot, well, blind spots can be fixed. But only if they’re pointed out, and only if people are willing to listen. Of course, Tim Burton doesn’t read this blog. And even if he did, he’s been successful for over thirty years, unlikely to change his ways. Perhaps it won’t be he who listens, but the new generation of creators he influences and who might build on what he’s done.

As fans, we need to have this conversation. We need to make it widely known that exclusion, dehumanization, and casual racism are not okay. It is valid and, hopefully, constructive criticism. It’s not about censure but improvement. Here at Geekquality, we often say amongst ourselves that we have a love/hate relationship with media. It’s not perfect, it has its problems, and if we confined ourselves to just the geeky stuff that isn’t problematic, we’d have nothing at all. We don’t want it to go away, we don’t want it to stop: we just want it to be better.

I want Tim Burton to be better.

Nailed it again, Rick! Great article.

A very fair and patient assessment. I stopped being a fan shortly around Big Fish, but it was headed that way since probably Ed Wood or Mars Attacks.

Pingback: The Round-Up: Oct. 16, 2012 | Gender Focus – A Canadian Feminist Blog

Personally, I do think that Burton has a definite problem in re: to race. A filmography like his and no PoC as protagonists, love interests, or heroes? I really can’t give him the benefit of the doubt. His penchant for casting only thin, white women as leading/supporting ladies is, frankly, disturbing.